Wool and Water

The Boy Scouts say: BE PREPARED. This video shows that wearing wool is great preparation for potential problems:

Backpacker Magazine published an opinion piece, authored by Casey Lyons, about the pollution caused by synthetic fleece. I was really interested in the first para:

"Fleece probably saved my life. I had just dumped my canoe in light rapids on a cool and overcast summer morning in northern Maine. I caught the throw bag, got hauled out, and started shivering despite the adrenaline from my first-ever whitewater swim. And then I did as I was told: I removed my sodden Patagonia, windmilled it over my head until it was dry enough to hold warmth, and put it back on. As we all know, synthetic fleece, even when wet, is a good insulator."

Casey Lyons got soaked during an "overcast summer morning". Who wants to suit-up in full polyester and jump in the river in winter? Based on my experience making the river-video, I'd say fleece was problem, not savior. (Somewhat ironically, Patagonia does make wool base layers, although I have never worn them.) I've recently seen other articles about how to handle the 'emergency' of getting soaked during a cool or cold-weather outing ... I focused on this article simply because it was the most recent. But the general idea is the same ... wet clothing is really dangerous and you need to:

- immediately change into the extra dry clothing you have stored safely in a waterproof container, OR;

- find a way to very quickly dry out the clothes you have on, OR;

- get to warm, dry shelter NOW

Really, I don't know what's up with all this. There's an old saying "an ounce of prevention equals a pound of cure" ... simply wear clothing that can handle the dunking ... so you carry on normally as soon as you exit the water.

When I saw similar cold-weather advice in a couple of other outdoor magazines, I wrote the editor of one of them that serious wool would have turned the dunking into a non-event. The editor invited me to file a story, which I intend to do, eventually.

Wool handles water much better most people know, particularly if their experience is with synthetics or cotton. Nature's designs are astonishingly sophisticated and tested constantly, everywhere, over eons.

With wool, Nature has created a fiber that behaves in ways that run contrary to what most people think is common sense. For example, wool can be thoroughly saturated with water and still dry to the touch ... this is key to wool's all-weather performance.

Please note there are related pages:

- Rain

- The Science of Wool

- Kitchen Table Experiments

- Wool and Humidity (physical effects of humidity on wool)

Wool enables sheep to comfortably withstand a very wide variety of weather conditions and maintain a body temp of about 102F (39C), just a little warmer than us, with minimal expenditure of energy. At WeatherWool, we thankfully use Nature's gifts ... and stay out of the way.

This discussion can get pretty long and involved, that's why we use a separate page. Also, I cannot claim that I really understand all of it. I've read a lot of material on this subject, and much of it I've read more than once or twice. (And here's something that's really crazy ... when I search for info on wool, I often find this website listed as a source!) But what I can say for sure is that I've worn wool in a lot of conditions, some of them quite strange, and been very impressed with the results.

Also, we tend to think WATER means LIQUID WATER. But water is also ice and vapor. Ice isn't relevant to this discussion, but the behavior of wool with respect to water vapor (humidity) is completely different from its behavior with liquid water. And that is very much a FEATURE. In biological systems, water can also, very critically, be a gel. I have a feeling that, eventually, water gel is going to provide an explanation of what wool can do with water.

This page doesn't really have much in the way of stories/examples ... it's more about the wool itself. We have separate pages where we relate some real-life stories about WeatherWool in the RAIN and WeatherWool for trekking. And we have a related collection of videos on this page.

BUT ... stories are memorable, so here's a couple of stories. When I was 12, 13 years old, we loved to play (American/Canadian-style) tackle football in horrendous weather ... cold, rainy, snowy, windy, muddy ... we got horribly filthy, and it's really something that my Mom (and I guess the other families, too) put up with it! I had an old wool jacket that was scratchy and not comfortable, but it was my football jacket and it always impressed me how that jacket worked better and better through the course of a cold, wet, muddy football afternoon.

In January of 2022, I was meeting with Giuseppe Monteleone, Plant Manager at American Woolen Company. AWC takes the lead in turning our clean fiber into Fabric. Giuseppe had just received samples from a company offering DWR -- Durable Water Repellent -- Finish. Giuseppe poured some water onto the DWR-treated fabric, and it beaded up real nice. And you could roll it around on the fabric, kind of like mercury. Nice stuff.

I took off my Lynx-Pattern All-Around Jacket, put it on Giuseppe's desk, and we poured a little water on the AAJ. The water beaded up and rolled around, just like we had seen on the treated synthetic sample from the vendor. We also poured some water on an old sample of our Duff Fabric that Giuseppe had handy. Same result.

Giuseppe and I were happy to see this behavior, and continued our meeting. Twenty or thirty minutes later, we looked at the samples again. The DWR and the old Duff had soaked through a little bit, but the new Lynx Fabric still looked as if we'd just poured the water.

Wool naturally repels liquid water, I think the ability of the Lynx to withstand the water longer than the DWR or the older Duff Fabric lies in the napping. Napping is a physical process, somewhat like brushing, that makes the surface of the Fabric fuzzy. We use a directional nap to help conduct water downward off our garments. Over time, the nap lies down, and this may have been why the Duff didn't perform as well as the Lynx. It may also be that the Duff simply hadn't been napped as much as the Lynx. We are always experimenting.

This is me, dressed in wool ... and barefoot ... fishing in steady, light rain, strong wind (15 knots / 28 kph) and cool temps ... both air and water at 55F/13C. The Atlantic Ocean surf was surging up to my thighs, and splashing above my waist, so chest waders would have been the normal choice, but they can be extremely dangerous ... and anyway, I always like to see what the wool can do. MidWeight Pants and FullWeight CPO Shirt were fine in the surf and fine in the restaurant afterward.

But exactly how does wool handle water so well? Here is what I've been able to pick up from the sources.

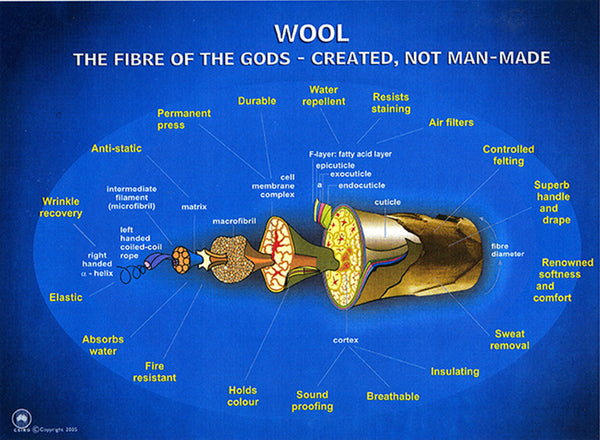

The structure of wool is very complex, and different parts of the wool fiber have different properties, as shown in the following diagram:

(The diagram above has been reproduced in slightly different form by a lot of people and I don't know who to credit for it. If anyone has info, please let us know! Near as I can tell, it's a modification of a diagram from Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, and as a government-sponsored agency I believe it's OK to use their material.)

Below is another version of the same diagram. The parts of the fiber are easier to see, and there is a sizing ruler added. A nanometer (nm) is a billionth of a meter, which is 10% bigger than a billionth of yard ... crazy small.

The outermost layer of the wool fiber, the epicuticle, repels liquid water. (The lanolin in wool also helps repel water.) So when you are out in the rain, even extended rain, or immersed in a river or the surf for a shorter time, the wool gets wet on the surface, like human hair would, but does not soak up any water. This behavior is completely different than typical cotton, which immediately fills up with all the water it can hold. From talking with probably thousands of people, I've learned that most people think (without actually thinking about it) that wool behaves like cotton, and have a very hard time accepting the tremendous differences between wool and other garment fabrics, such as cotton and synthetics.

Here is a very important way where wool's complex structure comes into play ... the interior of a wool fiber attracts water vapor. The surface of the epicuticle is scaly, and water molecules, particularly in the form of vapor, can slip through the spaces between the scales. Once inside the fiber, water molecules adsorb -- form hydrogen bonds -- to amino acids at the surface of internal structures within the fiber. Creating hydrogen bonds actually releases small amounts of heat (called the heat of sorption)! Also, and more importantly, the water vapor can condense inside the fiber. Water releases a lot of heat when it condenses from vapor into liquid. This is a pretty big deal for someone stuck outdoors in a humid cold. I think this behavior explains why wool is so popular on America's Gulf Coast ... it doesn't get all that cold there, but the humidity is crazy. I was in Mississippi once (another story I guess) for a serious snowstorm that shut down air travel from the Gulf Coast all the way up the Atlantic Seaboard. We got a few inches of wet, heavy snow. The temp was right around the freezing point, but it seemed MUCH colder because the humidity was so high ... and I come from New Jersey, where I thought we had humid cold! The joke was that I'd expected shirt-sleeve weather. It was the coldest not-truly-cold weather I've ever experienced.

Everyone has seen how water tends to stick together ... rain running down a window tends to form pathways that concentrate the flow. Same thing with the way water pools and beads on the Lynx Fabric in the short video clip above. Wool takes advantage of this tendency by shedding liquid water at the epicuticle, but admitting water vapor between the scales of the epicuticle.

During a rainy hike, a wool garment will shed the rain (liquid water), but adsorb internally the water vapor generated by the body in response to the effort of hiking. Many times I've hiked in warm, heavy rain, wearing on my torso only our CPO Shirt, and been amazed and delighted that I didn't get wet with sweat or rain.

This complex behavior is not useful only in rain. Wool clothing creates a great microclimate within which a human can be remarkably comfortable. On a wet day, after the rain, or just during high humidity, wool will adsorb humidity from the air, preventing it from reaching you, and keeping a relatively dry microclimate around you. And it works the other way, too ... if you are working hard enough to perspire, the wool can adsorb the water vapor coming off your body, preventing the vapor from condensing on your skin ... and so you don't have the impression of sweating. What's more, wool can do both these things at the same time ... such as during a rainy hike ... protecting you against moisture coming in, but also adsorbing the moisture produced by the body. And because the water is inside the woolen fiber, the outside of the fiber feels dry ... because it IS DRY. If the water was on the outside of the fiber, it could draw enormous heat from the body because wet skin can lose heat to the cold more than 20 times faster than dry skin. But trapped safely inside the fiber, the water does not wet the skin, and heat loss is drastically reduced. Holding liquid water against the skin is why COTTON KILLS.

One other factor that I don't really even know what to make of ... the fibers change as they pick up water:

- Wool fibers get thicker when they pick up water ... as much as 9% thicker. I don't know if this is good or bad

- Wool fibers become more flexible as they pick up water ... I also don't know if this is good or bad

- Wool fibers weaken by as much as 20% when they are full of water ... seems like this would have to be bad!

=============

What's also really great is that wool's ways of handling water not only help keep people warm in winter but also help keep people cool in the heat.

Of course, over time, the water adsorbed internally by the wool will dry out. I've gotten my wool plenty wet but hanging it overnight in a warm dry room is all it takes to get the moisture out. But it does dry slowly, in part because, while you are wearing the wool, the drying process costs heat, and Nature doesn't want a sheep using a lot of body heat to dry the inside of the wool fiber. I have a lot more to learn about the drying process, tho, because many times I've worn wet wool until it was dry and I never felt it was pulling heat from me. Others have said the same. And so I suspect Nature is doing something I don't understand. Perhaps the wool dries itself by excreting microscopic droplets of liquid water? That might be a way of drying without needing to pick up (from somewhere) the heat that had been released when vapor condensed into liquid.

In less abstract terms:

- Our friends in Mississippi feel wool's benefits as soon as they step out from their warm, dry homes into that bone-chilling Gulf Coast chill. When the warm, dry wool is suddenly moved to cool/cold and humid air, the wool will immediately begin to adsorb water internally, and produce heat while at the same time keeping the humidity from reaching the wearer. The wool buffers the humidity, adsorbs the moisture and creates a drier, comfortable microclimate around the wearer.

- When someone wearing wool suddenly starts working hard and creating sweat vapor, wool can adsorb the increase in water vapor before it condenses on the skin creating wetness ... wool captures and holds the heat contained within the vapor. Later, both the vapor and the heat will be slowly released. Feeling sweaty or clammy can be avoided. Also, again because wool will adsorb the vapor of perspiration, the wearer is cooled more quickly and kept more comfortable than if another fabric had been worn. People often talk about how synthetics wick moisture away from the skin. Wool goes one step better by adsorbing perspiration vapor before there is any water to wick.

- I have even seen claims that wool, compared to polypropylene, the most common synthetic, enhances athletic performance because wool allows the athlete to dissipate more heat, thereby avoiding exhaustion.When someone wearing wool experiences a sudden increase in humidity, wool can handle that as well, buffering the moisture and keeping the wearer comfortable.

One thing I read pretty often is that other fabrics dry quicker than wool. I'd say this is only half-true, because different materials get wet differently, strange as that may sound.

- Synthetics absorb very little water. Fleece won't actually absorb the water, but it will be wet and hold the water against you, where it will rob you of heat

- Cotton and other plant material absorbs all the water it can ... immediately ... death trap

- Wool adsorbs a lot of water ... slowly, and internally ... you may feel the weight, but you don't feel the water (sorry to be repetitious!)

The picture above was taken during a test in a pool. I laid out my old All-Around Jacket (same one that went in the river) on top of the water. At the same time, I laid out a cotton T-Shirt. The cotton shirt sank in seconds. The All-Around Jacket began to get wet very, very slowly, and it took 65 minutes to sink.

The picture above was taken during a test in a pool. I laid out my old All-Around Jacket (same one that went in the river) on top of the water. At the same time, I laid out a cotton T-Shirt. The cotton shirt sank in seconds. The All-Around Jacket began to get wet very, very slowly, and it took 65 minutes to sink.

Advisor Mike Dean tells me this (slow sinking) is a critical factor, and when he was field-testing his first piece of WeatherWool, he chopped a hole in the ice of a lake to see how long it would take to sink the AAJ. He got tired of waiting and held the jacket underwater with a stick ... and then put it on ...

Wool can adsorb (internally) a LOT of moisture. And it takes a long time to release that moisture. BUT ... the outside of the wool, the part of the wool we touch, dries off really quickly, and it feels dry because it IS dry. Synthetic materials will hardly soak up any water at all, and so they do dry off quickly. Cotton will immediately absorb all the water it can hold, and it will dry more quickly than wool, but cotton will feel damp, and will pull huge heat from you, until it is completely dry. The "wetting" behaviors of wool, cotton and synthetics are completely different, so it is hard to compare them on an "apples to apples" basis. But maybe that doesn't matter. What does matter is what clothes better protect you after a dunking on a winter day.

OK ... I love stories, so here is another story. A tester for the United States Army has tested our Anorak extremely thoroughly ... that is, i sent him one for eval, and he's been wearing it an awful lot for over a year as of March 2020. But his professional evaluation was that the Anorak is not suitable for regular Army because, he told me, the warmth to weight ratio is inferior to modern synthetic materials. And my response was ... "under what conditions?" ... People making these comparisons always seem to focus on dry conditions, when it is much easier to stay warm. What's the warmth to weight ratio after you climb out of a river, or even after a period of strenuous exercise?

And a real-life illustration (another story!) that came up unexpectedly: We recently picked up a large box of loom-selvedge from MTL. The selvedge is trimmed from the edge of the bolt of Fabric after the weaving is done. The selvedge is made with our yarn, and we are looking for things to do with it. The selvedge came in a large box and it took me a little bit to transfer the selvedge into a few smaller bags of maybe 20 pounds each. We use clear plastic garbage bags for things like this ... seeing what is inside the bag is very convenient. When I filled a bag, I set it aside in the sun and began filling the next. After the bags had been in the sun for only a few -- maybe 10 minutes the most -- I noticed the inside of the bags was wet with condensation. Running my hand inside the bag resulted in visibly wet skin. This was a shock. The selvedge had felt absolutely bone dry or I would not have put it into bags in the first place. And actually, MTL wouldn't have been working with it if it hadn't been dry. And yet, the Drab selvedge picked up enough heat from a few minutes in the sun that it began to release trapped moisture. The water vapor released by the wool quickly condensed on the inside of the bag because the air was cool even though the sun was strong. This was a tremendous and totally unexpected demonstration of the behavior of wool with regards to moisture and heat!

We have a related page, The Science of Wool, that has some of this same information, plus quite a bit more.

We'll exit by quoting a note sent to us by customer Tim (BIG THANKS!!):

Hello all of you!

The other evening it was cool and raining outside. I had let the fire die out in the stove because it was forecasted to [and did] get up into the 70's the next day. But the house was cool and therefore I put on one of my knit Wooly Pulley all wool sweaters over my lite Woolpower T shirt, and was comfortable. When the dogs needed to go out I simply went out in that same sweater. I did not get soaked but the sweater was wet, but not wet enough for me to think I needed to take it off once back inside. I sat down and within a few minutes thought,"What is going on? How did the house get this warm from when I got up to take out the dogs to now?" I thought this because I was getting too warm.....and walking the dogs had not been vigorous enough to get my body generating that much heat......partly because my dogs don't like getting wet and therefore they don't go very far with me to do their business when it is raining like it was. But then it occurred to me that I was experiencing, yet again, the fact that wool heats up when it gets wet!!! "Aha!", I thought, "I have experienced a "blind" study of the subjective fact about wool and water!" "Blind" because I wasn't even thinking about it and was caught off guard by how warm it got. I had to take the sweater off. Ha!

2 July 2025 --- Ralph